What Chariots of Shang China Can Tell Us About the Steppe?

The steppe vehicles were not particularly suitable for warfare, contrary to what is often claimed.

The discovery of spoked-wheeled vehicles in the Sintashta culture during the early 2nd millennium BCE has sparked significant interest, as these vehicles play a key role in various theories about Indo-European migrations. Despite this, the exact design and functionality of these vehicles remain a mystery, as no detailed archaeological remains have been found—only soil imprints of the lower part of the wheels have survived. Current theories about these vehicles are largely speculative, drawing from assumptions about the social structures of steppe societies.

Archaeologists M. A. Littauer and J. H. Crouwel, based on the dimensions inferred from the soil imprints, suggested that these vehicles would have been unstable and likely unsuitable for warfare or racing. They preferred a Near-Eastern origin of Chariots. (Archaeologists working in the Near East do not consider the Steppe to be the origin of chariots. This view has recently received support from some experts studying the Steppe, such as Russian archaeologist Stanislav Grigoriev, who highlights the issue of the incompatibility between the historical chronology of the Near East and the radiocarbon chronology of the Steppe.)1

At Sintashta, the wheel tracks and their position relative to the walls of the tomb chamber limited the dimensions of the naves, hence the stability of the vehicle. Ancient naves were symmetrical, the part outside the spokes of equal length to that inside. Allowing enough room for the end of the axle arm and linch pin on the outer side of the nave and for a short spacer on the inner side of the nave end to keep it from rubbing on the body of the vehicle, we are left with no more than 20 cm for the entire length of the nave. The shortest ancient nave of which we know on a two-wheeler is 34 cm in length, and the great majority are 40-45 cm. The long naves of ancient two-wheelers were required by the material used: wooden naves revolving on wooden axles cannot fit tightly, as recent metal ones do. The short, hence loosely fitting nave will have a tendency to wobble, and it was in order to reduce this that the nave was lengthened. A wobbling nave will soon damage all elements of the wheel and put all parts of the vehicle under stress. If the vehicle should hit a boulder or a tree stump, the wheel rim would lose its verticality and, so close to the side of the body, could damage that as well as itself. It is from the wheel-track measurements and the dimensions and positions of the wheels alone that we may legitimately draw conclusions and these are alone sufficient to establish that the Sintashta-Petrovka vehicles would not be manoeuvrable enough for use either in warfare or in racing.

Littauer MA, Crouwel JH. The origin of the true chariot. Antiquity. 1996; 70(270):934-939.

To explore this further, we can examine the evidence from China.

The introduction of "chariot" technology in Early Shang China (1400-1200 BCE) is generally believed to have spread through the Steppes.2 Unlike the soil imprints of Steppe vehicles, more complete remains of these Chinese chariots have been found, giving us valuable insight into their structure. However, it’s important to remember that these chariots are more advanced versions of the earlier Steppe vehicles, dating about 600-700 years after the first Steppe designs.

Archaeologist Alexander Semenenko notes that “considering the theories of bronze-age archaeologists regarding the spread of Sintashta-Petrovka-Alakul steppe "chariots" into China, it seems odd that the earliest Chinese two-horse, two-wheeled carts—dating from around 1300 to 1050 BCE—remained unsuitable for fast, maneuverable driving and standing combat. According to the logic of invasionist theories, these carts should have evolved significantly over the 800 years by the time they were adopted by the Shang Dynasty.”

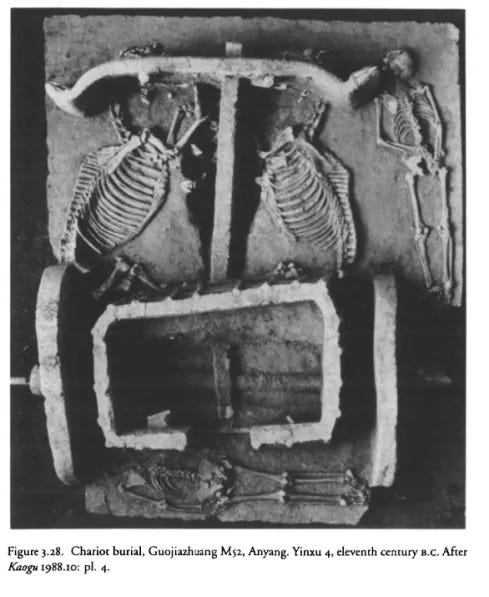

One of the earliest discoveries, labeled M52 and dated to the 11th century BCE, was unearthed in Anyang, the capital of the Shang Dynasty with burials of two horses and two human skeletons. This chariot is notably difficult to stand on, lacking any supporting handrails for the driver, making it unsuitable for warfare. Archaeologists who specialize in ancient Chinese studies have concluded that it was likely not designed for battle or rapid travel.

The absence of weapons from the burial and the decoration of the chariot were taken by the excavators to indicate that it was a passenger vehicle rather than a war chariot. It is not structurally different from chariots found in burials that do contain weapons, however, nor is there any reason to suppose that chariots taken to battle were plain (no matter how richly decorated the chariot might be, the team of horses that drew it was more precious). No chariot box with higher sides has been found at Anyang, and since the sides of the M52 chariot box would come only to the knees of a standing passenger, it seems unlikely that Anyang chariots were ridden standing. The use of such chariots in battle is uncertain. They could have served as showy vehicles for commanders or as transport for shifting special troops rapidly from one part of the field to another; kneeling archers could perhaps have fought from them. Though the chariot's passengers were sometimes armed, it does not follow that the weapons they carried were intended for use from moving chariots; in a society of warrior aristocrats, weapons are articles of apparel [...] Two unusual features of Anyang chariots are the large number of wheel spokes (anywhere from eighteen to twenty-six, as compared with four, six, or eight in the Near East) and the mounting of the axle not at the rear edge of the box but midway between front and back.

Bagley, Robert (1999), Shaughnessy, Edward L.; Loewe, Michael (eds.), "Shang Archaeology", The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC

One of the points raised by nearly all archaeologists of the Shang era is that the siderails of the chariot box only reach up to the knees of the rider, which may cause them to fall during sharp turns or at higher speeds. This seems to have happened in the case of a recent reconstruction of the Sintashta chariot, where the lack of support for the driver caused him to fall off the vehicle.

The overall decorative program on chariot M52 was probably designed to convey the image of luxury, power, and speed. The lacquered walls and floor of M52 are certainly more sumptuous than the decidedly more military chariots [...] The excavators suggest that M52 was a vehicle for elite conveyance and not a war chariot. I would tend to agree. The complete absence of weapons, the sumptuous decoration, and the hard floorboards all suggest to me that this vehicle was ridden in slow parade or not at all. Common to nearly all Bronze Age societies which employed the chariot was a burial ritual involving the interment of the vehicle with the deceased owner [...] This is seen throughout southern Russia, the Caucasus, Egypt, and Europe.. human sacrifice is much more common in the Chinese burials, where from one to three men were slaughtered and placed in the pit with the horses and the chariot.

Chariot M52 in particular, seems to have been lavishly decorated with red and black lacquer panels and sumptuous bronze decoration. This chariot, with its hard, wood floor and fragile yoke saddles, may never have been ridden into battle or taken out into the field to hunt. It may have been used only for ritual parade in state ceremonies, if it Was ridden at all.

The excavators of M52 did not find the top rail and had to estimate the final height. Some excavators of more recent finds (Guojiazhuang 1461167; Meiyuanzhuang MI) were able to recover the topmost rail of their chariots, confirming that 50 cm was indeed the maximum height of the box in Shang times, rarely surpassing the top of the wheels. The very short nature of Shang chariot boxes has led some scholars to suggest that these chariots could only have been ridden while kneeling, for it would be impossible to ride a horse-drawn vehicle at top speed when your only support came up to your knee. In contrast, many Near Eastern chariot boxes rose all the way to the hip.

Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. (2000). Wheeled vehicles in the Chinese bronze age (c. 2000-741 B.C.). Sino-platonic papers. University of Pennsylvania.

Although M52 dates back to the 11th century, examining older versions of chariots, as recorded in Oracle Bone inscriptions during the reign of King Wu Ding (who ruled from 1250 to 1200 BCE), reveals that the situation was either worse or not significantly different. According to the inscriptions, Wu Ding's chariot took one day to cover 30 km. For comparison, human athletes can complete a marathon of 42 km in anywhere from 2 to 6 hours, depending on their skill level. This slow movement can be attributed to the lack of siderails, which only ensured the rider's safety during slow travel.

Sun Zhenhao recounts the content of an inscription on a oracle bone from the time of Wu Ding (1324–1266 or 1238–1180, the first period in the classification of Dong Zuo-bin; see [49, p. 127]), which suggests that to cover about 700 li [a unit of distance in ancient China, 1 li ~ 500m), Wu Ding’s chariots took eleven days. This means the average speed was around 60 or slightly more li per day (see [14, p. 196]).. this distance amounts to about 30 km — a distance that a normal man, not an athlete, could walk in 5–6 hours. The speed of the chariots was clearly low. With a height of approximately 50 cm, it reached approximately to the knees of people standing on the cart, i.e. it could ensure their safety only during slow and calm driving. However, when driving fast, and even on a not very smooth surface, and there was no other at that time, the probability of flying out of the cart was quite large.

In one of the oracle bone inscriptions, it is said: "On the day of jia-wu (甲午) (the 31st day of the cycle. - sexagenary cycle), the king went to chase a rhinoceros. The horses and chariot ... struck a rock. Zi-yang, who was driving the king's chariot, also fell to the ground". From this, it is quite clear how unstable the position of the chariot riders was.

Kuchera, S (2010). "On the Issue of Technical Support for Shang-Yin Migrations." Society and State in China

True standing chariots only appeared in China during the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046–771 BCE), so the steppe peoples couldn't have had standing chariots before that.

During the Western Zhou, however, there is ample evidence for the presence of a handrail , which was higher than the side rails and traveled laterally across the box. Recent Anyang excavations (Liujiazhuang M348; Meiyuanzhuang M11M40) have shown that the handrail was already present in the late Anyang period. Based on Meiyuanzhuang M40, it was about 5 cm thick and was connected to the side rails, arching up and traversing the chariot box. It received further support from a flying buttress connected to the front rail. It may have risen as high as 25-35 cm above the side rails, allowing the driver to travel in a standing posture.

Barbieri-Low, Anthony J (2000)

The Shijing, a classical Chinese poetry book, includes a poem about a military campaign ordered by King Xuan to defeat the barbaric Xianyun nomadic tribe, who had threatened the Zhou Dynasty in the early Western Zhou period, likely before true standing chariots were invented. The steppe-chinese chariots are said to have covered only 30 li (about 15 km) per day. Even if they were not moving at full speed, 15 km per day seems quite slow. By comparison, a person walking at a normal pace of 5 km/h could cover 15 km in 3 hours, and chariots described by David Anthony would have covered the distance in just 30 minutes at their top speed.

Sinologist James Legge notes that all commentators agree that the poem’s reference to a month underscores the urgency of the campaign, implying they had little time to spare.

See Grigoriev (2023) Absolute chronology of the Early Bronze Age in Central Europe, Middle Bronze Age in Eastern Europe, and the “2200 event” http://dx.doi.org/10.14795/j.v10i1.817 and Grigoriev (2024) Absolute chronology for the transition to the North Eurasian Late Bronze Age and European Middle Bronze Age https://doi.org/10.52967/akz2024.1.23.79.95

Crouwel, Brownrigg & Linduff (2024) : "There appear to be no prototypes in early dynastic China for the first chariots and their draft and harness system. This strongly suggests that they were not locally developed but were indebted to forerunners from the Eurasian steppes"

The chariot platform is simply a small wagon with a section cut off for human entry.