Revisiting the Chronology of Surkotada

A case study on how outdated norms of Indian Archaeological establishment benefits Steppe theorists.

The horse is an important issue for proponents of the Steppe Hypothesis, according to which Indo-Aryan languages entered India only after 1800 BCE, during or after the Late Harappan phase, introducing horses previously unknown to people of the Mature Harappan phase. However, as previously explained in a post on Indus Quest on Substack, there is no archaeological evidence for an early second-millennium migration into India. This puts the issue of the horse at the forefront, requiring proponents of the Steppe Hypothesis to dismiss any finds of horse bones predating 1800 BCE.

The most cited case of horses in India comes from the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) site of Surkotada in Gujarat. Excavated by archaeologists J. P. Joshi and A. K. Sharma in 1974, the site yielded horse bones from all levels. However, these findings were dismissed as belonging to a wild ass, a tendency that traces back to paleontologist Frederick Zeuner, who, in his book A History of Domesticated Animals (1964), dismissed without evidence the horse bones as belonging to a wild ass found in the pre-Harappan settlement of Rana Ghundai, excavated by a team led by E. J. Ross.1

However, the Surkotada findings were later confirmed as belonging to the true horse by the leading archaeozoologist Sándor Bökönyi after a detailed examination. This conclusion was disputed by Richard Meadow, who insisted that it’s difficult to differentiate between the bones of various equid species. Unfortunately, Bökönyi passed away shortly afterward, before he could draft a response to Meadow. The debate between them is technical, and we will not delve into it in this post.

However, it is worth noting how differing standards of evidence are applied to determining the presence of horse bones in pre- and post-Late Harappan India. Meadow states in his article:

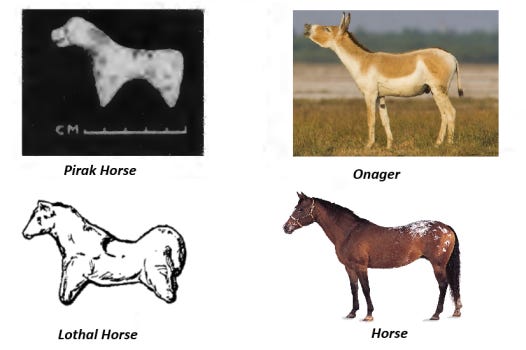

We do not doubt that horses came to South Asia at least by the end of the first quarter of the second millennium and perhaps even by the end of the third millennium. This is indicated by the figurine evidence at Pirak.

So, according to him, figurine evidence is sufficient to confirm the presence of horses in 1700 BCE, but any claim for an earlier period must be supported by an intensive archaeozoological examination of actual horse bones. (No bones were found in Pirak.)

Indo-European homeland studies has always been characterized by special pleading, red herring & circular reasoning as brilliantly documented by French archaeologist Jean-Paul Demoule in his recent book The Indo-Europeans Archaeology, Language, Race, and the Search for the Origins of the West.

It should be noted, however, that figurine evidence offers stronger proof of horses in India during the Mature Harappan phase. Below is an image comparing a horse figurine found in Lothal Phase IIIA with one from Pirak.2

Moreover, the frequency of horse bones does not increase in the post-Harappan phase, and no archaeozoological analysis has been conducted on these bones to confirm if they genuinely belong to horses rather than other equid species. By applying the same criteria used for horse bones from the Mature Harappan phase, there is no conclusive evidence of horses in India before the Mauryan period.

Looking only at the early historical layers, Taxila, Hastinapura or Atranjikhera (Uttar Pradesh) have indeed yielded bones of both the true horse and the domestic ass (let us note that the distinction between the two is no longer disputed here). But at other sites, such as Nasik, Nagda (Madhya Pradesh), Sarnath, Arikamedu (Tamil Nadu), Brahmagiri (Karnataka), Nagarjunakonda (Andhra Pradesh), no remains of either animal have turned up. There are also sites like Jaugada (Orissa) or Maski (Karnataka) where the ass has been found, but not the horse (Nath 1968). Finally, data available from sites that do come up with horse remains show no significant increase in the overall percentage of horse bones or teeth compared to Harappan sites such as Surkotada. If, therefore, the low amount of evidence for the horse in the Indus Civilization is taken as proof that that civilization is pre-Vedic, we may extend the same logic to the whole of early historical India. It seems clear that the horse was as rare an animal in preñas in post 1500 BC India.3

The_Horse_and_the_Aryan_Debate_M_Danino_2014.pdf

There’s another point that stands out in Meadow’s commentary:

We believe that we should expect to find the true horse in the subcontinent by the very end of the third or the beginning of the second millennium B.C. [..] it is important to note that Surkotada has dates that go into the second millennium, and the date of the "Harappan" layers themselves is not all that clear.

So according to him even if some of these bones are confirmed to be from horses, they would belong solely to the Late Harappan layer and not the Mature Harappan phase. Indeed, even those who argue for an earlier presence of horses in India accept the Surkotada date as 2100-1700 BCE.

However, this date does not hold up to closer examination. The chronology of Surkotada is based on radiocarbon dates reported by A.K. Sharma in a 1992 article.4

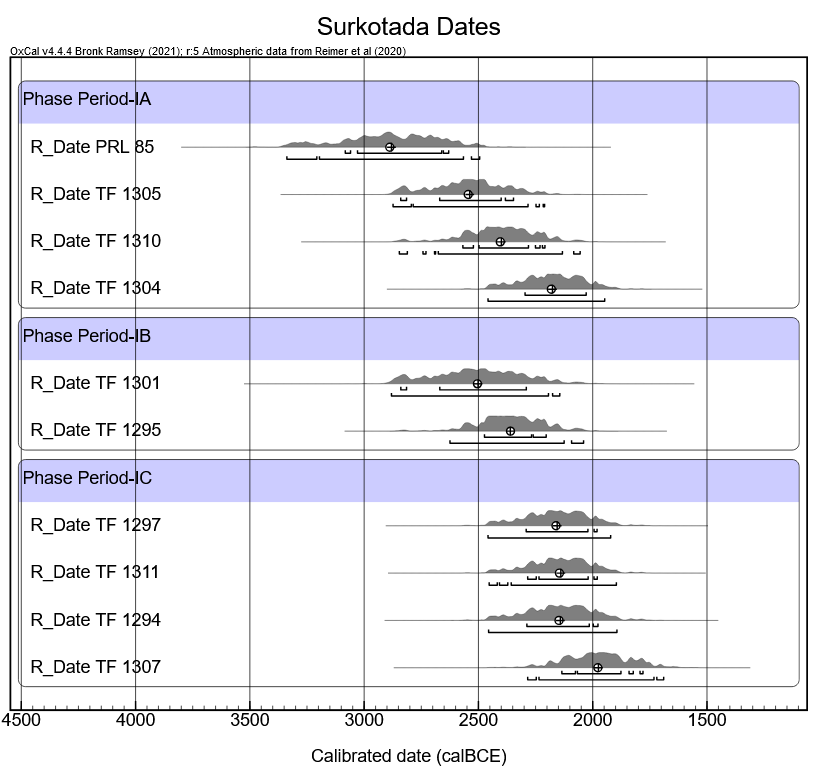

At Surkotada the bones of true horse (Equus caballus Linn.) identified are from Period IA, IB & IC. These periods have been dated on the basis of Radiocarbon determination as under.

Period IA

PRL 85- 4365±135 BP → 2315 BC

TF 1305 - 3890 ± 95 (4005 ± 100) BP 2055 B.C.

TF 1310 - 2810 ± 95 (3920 ± 100) BP 1970 B.C.

TF 1304 & 109 - 3645 ± 90 (375 ± 90) BP 1805 B.C.

Period IB

TF 1295 - 3635 ± 95 (3770 ± 95) BP 1940 B.C.

Period IC

TF 1297 - 3635 ± 95 (3740 ± 95) BP 1790 B.C.

TF 1311 - 3625 ± 90 (3730 ± 90) BP 1780 B.C.

TF 1294 - 3620 ± 95 (3730 ± 100) BP 1780 B.C.

TF 1307 - 3510 ± 105 (3610± 100) BP 1660 B.C.

With the correction factors, the dates fall between 2400 B.C. and 1700 B.C. In Period IA, Equus caballus Linn. was 1.2%, in Period IB 2.2% and in Period IC 1.49%. This shows that horse meat formed part of the diet only marginally because cattle bones predominate.

Sharma (1992) The Harappan Horse was buried under the dunes of... Puratattva 23: 30-34

The issue, however, is that these dates are expressed in radiocarbon years and cannot be directly compared with calendar years. To express radiocarbon dates in calendar years, they need to be calibrated using atmospheric data with a calibration curve. Earlier generations of Indian archaeologists often reported dates in radiocarbon years due to the unreliability of atmospheric data available during the 1970s and early 1980s.

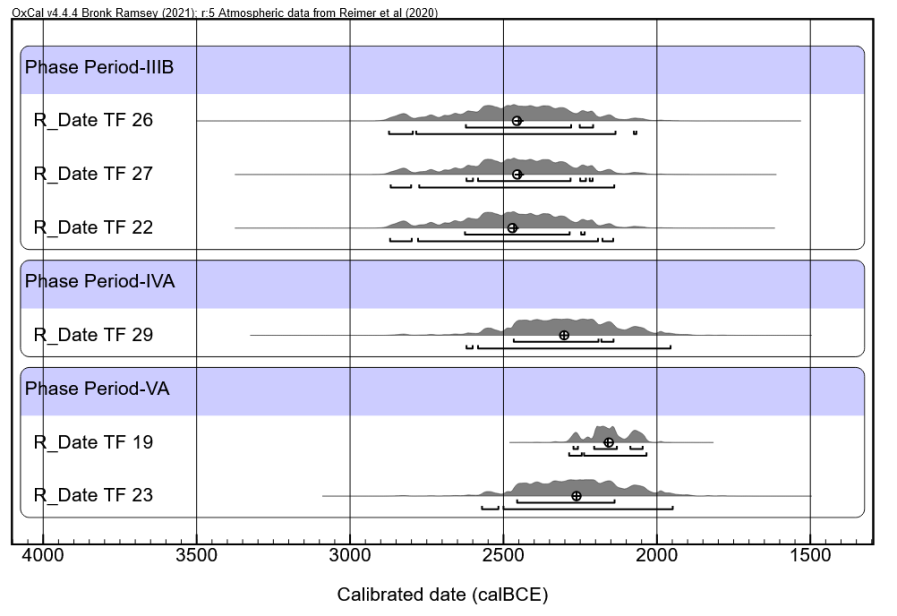

To accurately address this discrepancy, I calibrated these dates using OxCal v4.4.4 with the latest IntCal20 calibration curve.

The data used for calibration are the ones shown in parentheses and are based on the internationally accepted half-life of C-14 at 5730 ± 40 years. The initial dates outside of it are based on the outdated C-14 half-life estimate of 5568 ± 30 years.

As a result, the revised chronology of Surkotada aligns with typical IVC site chronologies, with dates ranging from 3050 BCE to 1900 BCE.56

Since horses are present in all phases of Surkotada, this extends their presence at the site back to 3000 BCE, lending support to even earlier finds of horses at Rana Ghundai.

The discovery of the bones of the domestic horse at this low level in the mound seems to us to be of very great interest. If, as Sir Aurel Stein and other experts state, these sites date from as early as the third or fourth millenniums B.C., interesting light is thrown on the antiquity of the domestic horse, for here it appears in the lowest stratum of the mound. It should be noted, moreover, that these remains are not, as might be expected, those of small pony-like animals. The teeth were examined by an expert veterinary officer before their dispatch to the Archaeological Department, and he assured us that they are practically indistinguishable either in structure or in size from those of our modern cavalry horses. This points to a very long previous period of domestication.

Ross, E. J., McCown, D. E., Guha, B. S., & Chatterjee, B. K. (1946). A chalcolithic site in northern Baluchistan. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 5(4), 284–316.

This was even accepted by the original creator of the invasionist theory of Aryans, Mortimer Wheeler.

The bones of a horse occur at a high level at Mohenjodaro, and from the earliest (doubtless pre-Harappan) layer at Rana Ghundai in northern Baluchistan both horse and ass are recorded. It is likely enough that camel, horse and ass were in fact all a familiar feature of the Indus caravans.

Wheeler, M. (1968). The Indus Civilization: Supplementary Volume to the Cambridge History of India (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press, p. 62.

The horse figurine belongs to sub-phase IIIA of Lothal (based on a 5-phase classification proposed by SR Rao). Calibration of existing radiocarbon dates suggests that Lothal IIIB can be dated to ~2450 BCE so the horse figurine must precede this. Data from Kusumgar et al (1964).

The period of excavation being considered here from Nath (1968): Nasik (1500-500 B.C.) Nagda (1500-200 B.C.) Arikamedu (20-50 A.D.) Brahmagiri (1000 B.C.-200 A.D.) Jaugada (400 B.C.-200 A.D.) Brahmagiri (1000 B.C.-200 A.D.).

Originally published in Surkotada’s excavation report.

TF-1301 data is taken from: TATA INSTITUTE RADIOCARBON DATE LIST XI which is converted from Libby’s half-life (5568 ± 30 years)

PRL-85 is misprinted in the article. The correct date is 4265 ± 135 reported by JP Joshi. https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.57533/page/n47/mode/2up